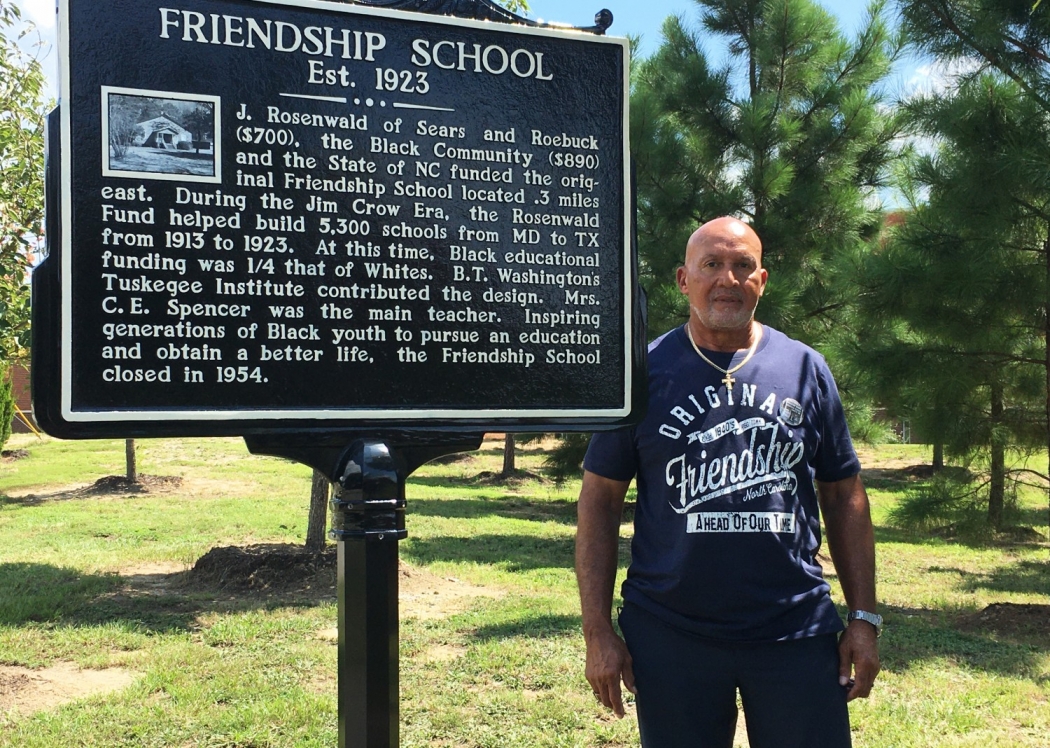

Friendship and perseverance were on display during a Sunday ceremony to dedicate a historical marker telling the story of a small segregated school.

After a two-year campaign by supporters, the marker was unveiled on Sunday, Aug. 22. Located on Humie Olive Road in Apex, the marker is next to the current Apex Friendship Middle School and down the road from the original Friendship School building, built in 1923.

Roughly 50 supporters, including Apex Town Council members, Wake County School officials and three former students of that first Friendship School, gathered to honor the community of Friendship and the lasting impact of the school where generations of Black children were taught.

“Today we make the connection between that base school and these beautiful new schools, as we strive for excellence for education, going into the future,” said community organizer Larry Harris, in remarks at the ceremony.

Rebecca Ashley, media coordinator at Apex Friendship High School, and Larry Harris, with the Friends of Friendship, unveil a historical marker commemorating the 1923 Friendship School on Sunday, Aug. 22. The marker, near the high school and Apex Friendship Middle School, is down the road from the first Friendship School, where Black children were taught until it closed in the 1950s.

Harris, along with the Friends of Friendship, has led efforts to erect historical markers commemorating three school houses from the Jim Crow era. These schools were built with the help of philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, so African American children could be educated.

“Yes, it’s a marker, but it’s more than a marker. It’s a remembrance of the blood, sweat and tears of years past,” Harris said.

From 1913-1932, some 5,300 schools were built in 15 southern states, and with more than 800, North Carolina had the most. In Wake County alone, 27 Rosenwald schools were built.

The Friendship School was special to Harris, because his mother taught at the school and because his family has lived in the area for more than a century — since free Blacks, Native Americans and white Quakers agreed to live in peace and to call their community Friendship. Those deep roots were helpful when Rebecca Ashley, media coordinator at Apex Friendship High School, contacted him for help researching local Rosenwald schools.

Wake County Schools had launched a county-wide effort to preserve local history, “Respecting Our History, Building Our Future,” in 2019. Media coordinators were asked to document the history of local segregated schools, many built with money from the Rosenwald fund, and to interview teachers and graduates of these schools.

“The school system understood that the history could be lost simply due to the passing of time,” Ashley said during the ceremony.

“We’re grateful that the marker commemorating the Friendship School is up, but our work is certainly not done. We will continue to preserve the history of the Friendship community as well as the school.”

The Friendship School closed in the 1950s and eventually became a private home. The nondescript structure now stands empty.

Plans are in the works to create an interactive display with artifacts and a high school course based on the history of the Friendship community, Ashley says. There will also be a mural at the middle school, highlighting students of the original Friendship School.

“The core of our efforts will be the ideal established by the founders of Friendship, which centered on unity among all, regardless of race, ethnicity or any other differences,” she said. “This community rose above social and political pressures, and we strive to do the same by preserving and nourishing the spirit of friendship.”

The Friendship School is one of the few Rosenwald schools still standing in Wake County. Of the 5,357 schools, shops and teacher homes constructed between 1917 and 1932, according to the National Trust for Historic Places, only 10-12% are estimated to survive today.